The Cleveland Planning Commission (CPC) is preparing to introduce form-based codes, an alternative to the zoning codes the city has relied on for generations. This shift will transform the decision-making processes that determine what gets built and where. Here’s a look at what it means.

What is form-based code?

Form-based code (FBC) is a different approach to land-use guidelines, or zoning.

For about a century, zoning codes in Cleveland and most other places have focused on land use restrictions — what you can and can’t build on a specific property. These restrictions are organized into three main categories: residential (houses and apartments), commercial (retail stores, restaurants and bars, office buildings) and industrial (manufacturing and related facilities).

FBC also regulates land use, but its key principle is the form of buildings and how people interact with them rather than simply what happens in them. Form-based codes “address the relationship between building facades and the public realm, the form and mass of buildings in relation to one another, and the scale and types of streets and blocks,” according to the Form-Based Codes Institute.

The switch to form-based code is intended to:

• Replace the dense and confusing existing code with clear language and images that explain up front what’s allowed and required

• Reduce the time between applying for and receiving a permit for development

• Allow more mixing of land uses, so that, for example, it’s easier to build stores, offices and housing in the same area, as well as a greater mix of housing types

• Encourage the development of walkable neighborhoods in all parts of the city

• Give residents more control over their communities

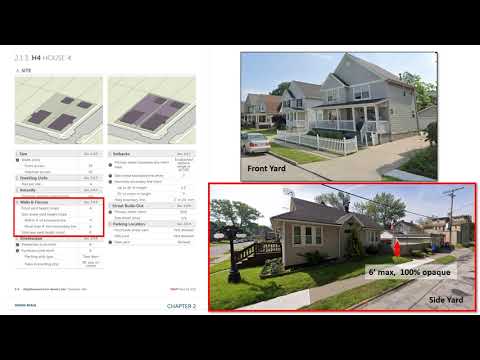

Form-based code is made up of many small districts with their own permitted uses, height limits, setbacks, etc. Residents help the Planning Commission decide which districts should go where. The districts are explained in detail in this draft of the code, and one of them, H4, is reviewed in the CPC video below.

What’s wrong with the existing zoning code?

When the current code was adopted in 1929, the priorities were “separating residential areas from the ill effects of neighboring factories, managing the reality of a populace in love with the automobile and providing for greenspace in a rapidly developing city,” the Cleveland Planning Commission explains.

In Cleveland and elsewhere, zoning codes were intended to isolate residential, commercial and industrial areas from each other. In the early to mid-20th Century, that made sense. But it not only reflected the increasing reliance on cars, it also spurred suburban sprawl.

By the 1950s, the City of Cleveland’s population had begun to decline. Manufacturing jobs peaked in 1969, then dwindled rapidly through the ’70s and ’80s. Attempts to adapt the zoning code to such changes resulted in a code that is “layered and cumbersome to navigate,” according to the Planning Commission.

“In many ways,” CPC writes, “the zoning code is at odds with the vision of what Cleveland will be in the 21st Century.”

This is not just a problem in Cleveland. Strong Towns, a non-profit news website focused on development, likens zoning codes to a city’s DNA.

“If your city is like most North American cities, its DNA is broken,” Strong Towns asserts in an essay advocating for FBC. “Zoning practices adopted nearly everywhere over the course of the 20th Century—a giant, unprecedented, and untested revolution in city planning we’ve dubbed the Suburban Experiment—have enshrined a set of destructive planning practices that lead to spread-out, unwalkable, and financially insolvent communities; to housing shortages and onerous restrictions on local businesses.”

What is form-based code supposed to accomplish?

“This code will help Cleveland foster a community built around healthy, walkable neighborhoods, alternative modes of transportation, and diverse housing options,” according to the Planning Commission’s FBC web site.

Let’s take those one at a time.

‘Walkable neighborhoods’

Chief City Planner Shannan Leonard said FBC will “make Lorain Road legal again.”

In a presentation she prepared for community groups, Leonard showed aerial photos of a block of Lorain Road and a block of Clark Avenue. On Lorain, the buildings are close together and easy to reach on foot. On Clark, the buildings — many of which are chain restaurants — are spread out and surrounded by parking lots.

Most of the development on Lorain preceded the current zoning code, before parking lots were required. And it has stayed largely the same, in part because the code makes it difficult to build anything new there or change the use of a property, like, say, from retail to housing, even if storefronts are abandoned and housing just makes more sense now.

This is called infill development, building on vacant or under-utilized land in dense areas. It’s not impossible, but it requires a lot of variances (exceptions to the code), and that process takes more time than many developers are willing to commit, especially in a neighborhood that isn’t already growing.

The development on Clark came long after the zoning code was adopted, and it reflects a simple truth about one of its effects: What’s easy to build is what gets built, whether it fits the surrounding community or not.

‘Alternative modes of transportation’

Form-based codes’ impacts on transportation are indirect but potentially significant. The most important change is doing away with parking minimums for new development. On its FBC page, the CPC is blunt in its assessment of the longstanding policy of requiring new parking lots to accompany housing and retail construction, based on what generally turn out to be outdated and arbitrary formulas.

“There is no magic or even data to back up the ratios in Cleveland’s existing code,” CPC said. “In fact, most ratios are just borrowed from other similar-sized cities. And those ratios were borrowed from those cities’ peer cities in a time-honored tradition that goes all the way back to Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller just trying to sell more cars and gasoline.”

Buffalo, New York, dropped parking minimums in 2017. A study of some building projects that followed found that several of them shared parking, which made development more feasible. The authors concluded: “In the absence of [minimum parking requirements], off-street parking lots can transform into parks, shops, workplaces, and residences.”

Parking lots are expensive to build and maintain, and those costs get passed along to renters and consumers, even ones who don’t drive, said Angie Schmitt, a Cleveland-based planning consultant, author and journalist.

But eliminating parking minimums from the zoning code won’t necessarily make a big difference. Banks often require new parking when financing development, she said.

“In Seattle and some other cities, there are whole apartment buildings with no parking, but they’re on new transit lines,” Schmitt said. “But I think development community financiers here are a little more conservative, and in some ways it makes sense because our transit system just isn’t awesome.”

‘Diverse housing options’

Eliminating parking minimums could also encourage new housing development. Sightline Institute, a nonprofit sustainability group, found that “studies from two cities [Buffalo and Seattle] observed that in the years following [zoning] reform, 60 to 70 percent of new homes would previously have been illegal to build.”

Cleveland’s FBC also would relax a lot of regulations related to housing.

Leonard explained how in a presentation to the Cleveland Planning Commission in June:

“Under the current code … it’s really hard to build a variety of housing typologies due to minimum lot size” and other requirements, Leonard said. But FBC “promotes a variety of housing typologies, mainly the missing middle.”

The missing middle refers to housing options between the two typically found in cities, single-family homes and apartment buildings. It includes duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes, cottage courts, pocket neighborhoods and live-work. You can see examples here.

The Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization, created an animated web page to show the types of housing development made possible by zoning reform.

FBC should also make it easier to buy existing homes in Cleveland by removing a barrier to securing a mortgage. Many old homes in Cleveland do not conform to one or more elements of the current zoning code. Banks are often reluctant to approve loans to buy those homes, because if they are badly damaged or destroyed, they can’t be rebuilt without variances, a costly process. (This also adds an incentive to sellers to take cash offers from out-of-state investors who buy up homes to either flip or rent.) But with FBC, “all lots on record will become legal at the time that the code is adopted in that area,” Leonard explained.

Will property owners have to make changes to comply with the new code?

No. Only future changes to the property will be affected.

Is this related to Mayor Bibb’s plans for a ‘15-Minute City’?

Sort of. The Cleveland Planning Commission has been working toward form-based code since 2015, when Frank Jackson was still mayor. But FBC presumably would make it easier to achieve the goal of the 15-Minute City concept, which is designing neighborhoods in which residents can get to school, work, stores and other typical daily stops in 15 minutes or less on foot, bike or public transit. For more, read these explainers in The Cleveland Observer and Cleveland Magazine.

FBC could also complement Bibb’s proposed Site Assembly and Development Fund, which would purchase properties, clean up polluted sites and perform other work to prepare land for redevelopment. The plan is backed by $50 million from the city’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds.

When will form-based code take effect?

The plan is to introduce FBC gradually, starting with three pilot districts: Detroit Shoreway/Cudell, Hough and an area around the Opportunity Corridor. (Maps available here.) These areas were selected because each has a wide range of building types and land uses, and a lot of development is expected in these areas in the near future, allowing the CPC to see the effects of the zoning change more quickly.

The Planning Commission has been holding community meetings in the pilot areas. The next two are:

Detroit Shoreway & Cudell: Wednesday, Sept. 20, 5:30 to 8:30 p.m. at the Commons at West Village, 8301 Detroit Ave.

Hough: Tuesday, Sept. 26, 5 to 7 p.m. at Fatima Family Center, 6600 Lexington Ave.